“It was the first of November 2016,” Marie recalls. “Peter had a major stroke and everything changed overnight.”

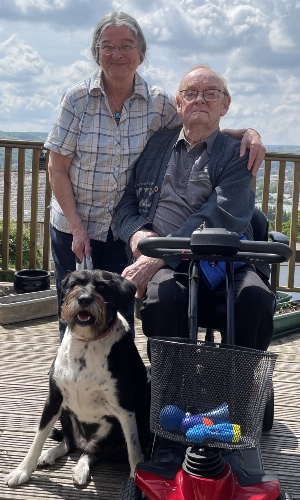

Marie and her husband Peter had been making plans. Having met around 20 years earlier, when Peter attended a university course taught by Marie, the couple had enjoyed a contented life together filled with their shared interests of gardening, politics and dogs. In 2016, Marie was on the verge of retirement, with her and Peter looking forward to starting a new project together.

“I took Medieval History, but when I was working there was never much time to write the books I wanted to,” says Marie. “Peter’s a very good photographer, so we were going to go around the country for Peter to take photos of the monasteries I was going to write about. “Of course, that never happened.”

Inadequate support

“Peter was in hospital for seven weeks,” says Marie. “When he was discharged, he was entitled to six weeks of social care, but it was pretty poor. The two carers would either be incredibly early or extremely late, so Peter would often be nodding off in his wheelchair when they arrived. They would run into the house, and 15 minutes later they’d run out again. It’s not their fault – that’s all the time they were given – but it left me thinking, ‘well, I can do that’.”

Marie had some experience of basic care from working in a hospice years earlier, so decided to take on the role of being Peter’s primary carer. After learning that she’d have to wait months to get financial help with making adjustments to their home, Marie also felt she had no choice but to manage and pay for the necessary remodelling herself. “As soon as Peter was home, the first thing I had to do was alter the bathroom,” she says. “I had the bath taken out so that Peter’s wheelchair could run into the shower, like a wet room. Then I had an internal stairlift installed.

“The carers were still coming in at that point and I remember one of them saying, ‘that’s very quick! How long is the waiting list?’. The simple answer to that is that they’ll come tomorrow as long as you’re paying for it yourself.”

Peter worked from the age of 15 to 65... Yet in terms of social support since he had his stroke, there’s been hardly any.

After two years of caring for Peter on her own, Marie looked into the possibility of a temporary change of scenery for both of them. But when Marie rang her local council to arrange some respite care, she once again found that support was lacking. “The person I spoke to said, ‘have you got £23,000?’. And once I said yes, he told me that as I’d have to pay for respite care myself, I may as well organise it myself.

“I pointed out that I’d need help to get Peter out of the house and down the steps to the road, and when asked if social services could help with that, I was told no.”

Out of options but determined to give Peter some extra freedom, Marie paid to have an external stairlift fitted – taking the total cost of her self-funded home adjustments to around £65,000.

“I wouldn’t for a second expect the state to pay on that scale,” says Marie. “But Peter worked from the age of 15 to 65. He paid National Insurance all his life. Yet in terms of social support since he had his stroke, there’s been hardly any.”

Care staff are undervalued and underpaid. There needs to be a change in mentality.

A situation that needs to change

Aware that she’s not alone in facing difficulties with finding support, Marie is adamant that the system needs to change. “I think one of the basic problems in health and social care is compartmentalisation. Each part of the health and social care provision discharges its obligations, but then their job is done. So, when Peter was discharged from hospital, that was it – there was no continuity.

“And because the funding of social care goes through local councils, and local government is starved of cash, that also impacts on the ability to provide care. Even if the local council wishes to provide adequate or excellent social care, it hasn’t got the means to do so. Care staff are undervalued and underpaid. There needs to be a change in mentality.”

Marie hopes that this change in mentality will extend to unpaid carers, too. Although there was no doubt in Marie’s mind that she would care for her beloved husband, she can’t help but feel that the contributions made by unpaid carers like her go unappreciated by the Government and wider society.

If it comes to a point where Peter’s got to have more care, I’ll deal with it then. It’s just a black cloud on the horizon that any time could come into view.

“Peter was very poorly when he came home, and of course I was prepared to look after him, but it’s just the fact that they expect people to do it,” says Marie. “I’ve saved the Government thousands of pounds a year, and they give back next to nothing.”

While Marie keeps hoping that social care will be taken seriously in the coming election, on a day-to-day basis her life with Peter carries on – “we manage as we are, and muddle along”. Now aged 74, Marie understands any changes to the couple’s finances or health may impact her ability to care for her 85-year-old husband.

“I’m fortunately fit and well for my age, but the thing is, whether you feel well or ill, you’ve got to get up and keep going. If it comes to a point where Peter’s got to have more care, I’ll deal with it then. It’s just a black cloud on the horizon that any time could come into view.”

Support for carers

If you're caring for a loved one, we have information and advice about your options and the support available.