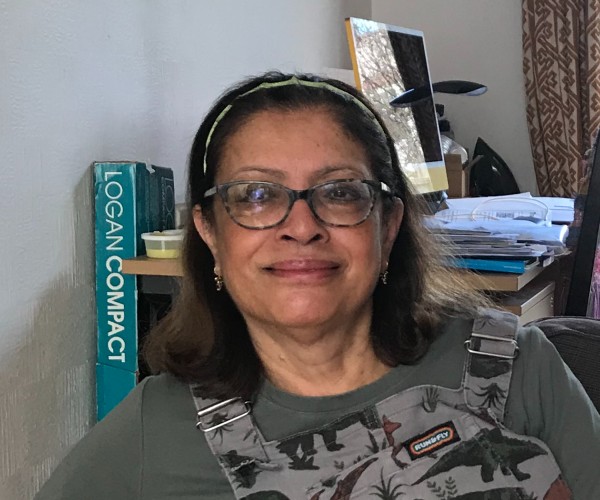

Sajeda was born in Kampala, Uganda’s capital city, where there was a large mosque that she attended with her family. During celebrations, people would sit on the floor together around vast trays of food, drinking ‘Sherbet’, a pink rose flavoured milky drink.

These are her early memories of Ramadan. They were happy times.

These are her early memories of Ramadan. They were happy times.

Today, 69-year-old Sajeda is unable to fast during Ramadan. She had part of her left lung removed after being diagnosed with cancer and has been diabetic for 20 years. She remains committed to Ramadan, though, regularly visiting her local mosque in north London and bonding with people in her community.

Islam was a central part of Sajeda’s life. When her mother’s side of the family arrived in Uganda from India and settled in a small village, they first built houses of brick and mud, then they built the mosque. It wasn’t like other mosques, though. Sajeda’s family are Ismaili Muslims and call the mosque Jama’at Khana, meaning ‘People’s house’.

Learning about Ramadan

Sajeda’s awareness of Ramadan began as a child when she noticed the adults around her weren’t eating during daylight hours. While she would eventually become adept at fasting, her early efforts failed because she’d “cheat like mad”, unable to resist the snacks found in the family’s larder.

“Ramadan was a happy month,” says Sajeda of her early experiences. “There was a focus on food, whether that’s abstinence from food or when we broke the fast in the evenings with special dishes we might not have ordinarily. Then at the end of Ramadan, it’s Eid, which is when you got new clothes and were given money. The children would go from house to house to take people sweets, which would result in being given more money.”

There was a focus on food, whether that’s abstinence from food or when we broke the fast in the evenings with special dishes we might not have ordinarily.

Challenging times

In recent years, Sajeda has experienced the challenges that come with later life. Two years ago, she lost her mother. During lockdown, the two of them would ‘attend’ daily prayers together over Zoom. Sajeda regrets that COVID restrictions prevented her mother from having a traditional funeral, during which the coffin is open, allowing the head of the mosque to sprinkle holy water on the face of the deceased and attendees to pay their respects. “We just went directly to the cemetery,” recalls Sajeda. “It was very unusual.”

Thankfully, Sajeda has happy memories of celebrating the morning of Eid with her mother over the years. Together they’d eat a traditional breakfast of vermicelli sweetened with nuts and raisins, along with poppadom. “All the family would come here for lunch,” Sajeda says of busier, more sociable times. “We’d cook big feasts, and the children would be given money. It’s not been happening for the last two years, though. Since COVID, many people don’t have the energy.”

Loss and ill health have inevitably led to changes in Sajeda’s relationship with her faith as she’s grown older. “It’s been up and down. There are times when you question things, but at the back of your mind your faith is there and when you need it, you turn to it.”

The importance of charity

Islam has instilled a steadfast sense of charity in Sajeda, as it’s a cornerstone of the faith. Her family in Kampala would always send food to poor local people during Ramadan, as a powerful reminder that it’s more important to give. That dedication to helping others has continued into adulthood. After retiring from her job teaching science to master’s and PhD students at University College London, Sajeda busied herself as a volunteer, tirelessly feeding homeless people and asylum seekers. “I see it as a repayment,” she explains. “When I came to this country, I was an asylum seeker, and I was welcomed.”

Sajeda’s love of cooking, and of teaching, brought her to Age UK Barnet in 2014. She started by volunteering in the kitchen but was soon running her own classes. She gets joy from how happy the successful completion of a recipe makes people. She recalls leading one of the men’s classes, like the one attended by celebrity chef and businessman Levi Roots in 2018. “You’d have one of the men tell you they’d made a cake for their daughter-in-law, and she’d love it, with a huge sense of pride.”

Ideally, Sajeda would like to make food and deliver it to older people who remain in their homes, permanently changed by the pandemic, or struggling to afford the essentials because of the cost of living crisis. Sadly, her ill health means she’s unable to, so she’s concentrating on returning to teaching. “It makes my life worth it. It gives me a purpose. If I didn’t do it, what would I do? I don’t want to be lying down at home doing nothing. It feels good to make people happy.”

There is a very important point to life: it’s to help other people.

A time for reflection

Given her inability to fast during Ramadan, what does Sajeda use this important time to reflect upon? “Life,” she suggests. The first person she helped after she retired was her uncle, her mother’s brother, who no one had heard from for some time. When family members eventually visited him, they discovered he was delirious from malnutrition and dehydration, and his home had fallen into disrepair. Sajeda took over his care, travelling an hour-and-a-half each way every day to visit him. Eventually he went into a care home. There, the cook, who was from Goa, would prepare Indian meals for Sajeda’s uncle, which brought him joy towards the end of his life.

While food remains an important part of Sajeda’s life, so too do its big questions. “Age often makes you wonder what the point of life is,” she says. “But there is a very important point: it’s to help other people.”

Will you join us?

Every day, our volunteers give their time and effort to make an incredible difference to the lives of older people. Without them, we couldn't be here when we're needed most.