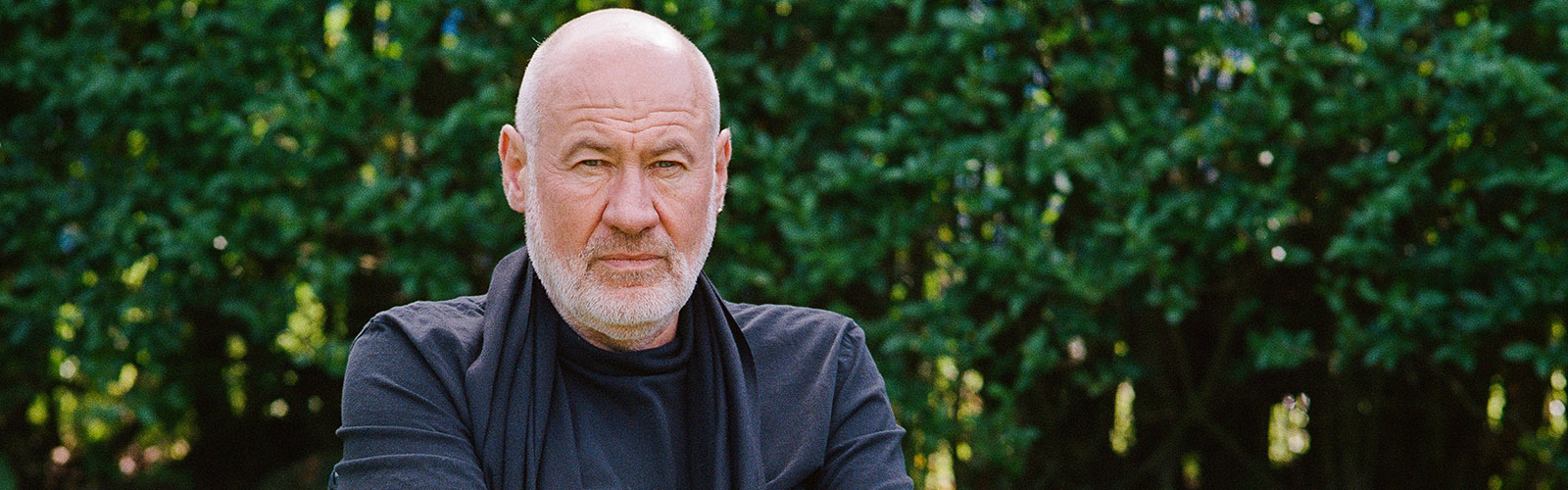

Derek William Dick, better known by his stage name Fish, is the former frontman of rock band Marillion, famed for their hits Kayleigh and Lavender. Now aged 62 and having made music for four decades, Fish has decided his latest album Weltschmerz will be his last. And while this is so he can explore new avenues in his writing, Weltschmerz – the German word for a feeling of melancholy and world-weariness – grapples with the challenges of age.

Personal subject matter

Fish has always been ambitious when it comes to the breadth of his songwriting, which is why making progressive rock – a genre known for its long songs – has always appealed to him. His 2013 album A Feast of Consequences, for example, featured a suite of tracks about World War 1, which saw the Scotsman throw himself into a great deal of reading, one of his favourite pastimes, to help research the epic stories he wanted to tell.

More recently, however, Fish has brought his lyrical focus back to the here and now. “I wanted to write about the world we live in, but not big banking and big Government,” he explains. “I wanted to look at the pains of the world as experienced at street-level.” Fish has certainly been no stranger to pain in recent years, having lost his father in 2016, with real life providing him with more than his fair share of material.

“I found watching my father’s last few months very difficult,” he reveals. “My father had been a very strong, powerful person, and it was challenging to see him become reliant on others, and stubborn, and the fight change in him. I felt an overall depression creep up in me. It wasn’t his actual death that got to me, but the end game of it.”

It wasn’t [my father's] actual death that got to me, but the end game of it.

A harsh reminder of time passing

Weltschmerz features several songs that deal directly with that period. One of them, Man With a Stick, is directly inspired by his father, while Little Man What Now was informed by the depression that took hold of Fish after his father's death. “I got involved in the funeral arrangements and I was there for everyone else – my mother, my daughter, assuming the role of the new guy in the flat cap who’s in charge of the family – but I wasn’t there for myself. Then, for the next 6 to 7 months, I realised there was so much I hadn’t addressed."

What were those things?

“I had a spinal operation at the end of 2017, then I had a big shoulder operation, and I became aware I was physically weakening. With age you can develop an element of fear that you’re no longer as physically strong and capable as you were. That realisation, when it creeps in, can become very depressing in itself.”

Garden of Remembrance

Fish’s mother has been living with him and his wife in Haddington, East Lothian – about 20 miles east of Edinburgh – for about 18 months. More recently she has shown signs of cognitive decline, though she hasn’t had an official diagnosis yet, which makes Fish cautious on the topic. “I never heard the word ‘dementia’ when I was a kid. People got old and you’d hear someone say, ‘Oh grandad forgets things!’” Fish’s certainty his mother has dementia is strong enough for him to have written the song Garden of Remembrance, inspired by gardening's ability to anchor his mother back to more lucid moments.

“She has what I call ‘rabbit hole moments’ where she’ll get a bit lost, but the weather or doing the weeding can bring her back,” reveals Fish, who found recording the song difficult, given its subject matter. “When you get emotional, your voice chokes. I was recording the song knowing my mum was abour 15 metres away, imagining what is going to happen to her next. My wife and I also both love gardening, so I was thinking about the future for us too. What happens if my mind goes and I don’t recognise her, while she's left with a lifetime of recollections?”

Despite being made before lockdown, Garden of Remembrance's video (below), which features people separated by glass, predicted the imagery seen in recent months of families socially distancing and having to interact through windows. “It was scarily prescient – it really hit me,” says Fish, who's interacted with fans in recent months via 'Fish on Friday' on Facebook, a weekly event in which he takes part in live Q&As and shares tracks.

You’re dealing with someone who, physically, is the same person, but mentally they’re changing before your eyes.

Fear of the future

Given the importance of words and structure in Fish’s life, not to mention the fact he’s got a near-photographic memory, the idea he could be robbed of these gifts in future is cause for great concern, both emotionally and intellectually. “I’m petrified of losing memory and my ability to communicate properly,” he admits.

“It also makes me think about the ways we deal with those who have dementia. You’re dealing with someone who, physically, is the same person, but mentally they’re changing before your eyes, sometimes subtly, and others in ways that really throw you. Trying to keep that level of understanding towards that person is difficult.”

Dementia

A dementia diagnosis can be overwhelming and you may well have worries about what happens next. From keeping well, adapting your home and getting support, Age UK can guide you through it.

Moving forward

Given Fish’s fears about his gifts being taken away, shouldn’t he appreciate them while he still has them? Would he reconsider Weltschmerz being his final album? “No,” he replies immediately. “There are only so many melodies in the world. I've got screenplays in my head. I've sat on tour buses for years and formulated plot lines and only written some of it down. Then there's any autobiography or memoir I write. I want to move on an explore something else. I might fall flat on my face, but I have to do it."

That's further down the road, though, so for now there's one final question: what would Fish consider the ultimate compliment someone could pay Weltschmerz? “Someone saying it makes them cry.”

Weltschmerz is released on 25 September.