Howard Jacobson’s latest novel, Live a Little, is about a developing romance between two people in their nineties. At 76, you might think the author and public intellectual is better placed than ever to write about finding love in later life. “It was never the plan,” he tells us. “When I’m writing I just jump in and see what happens.”

Howard didn’t have his first book published until he was 36, and his first novel at 40, which he considers a belated start in the profession. “I’m surprised I’ve produced so many books,” he reveals, sat on the sofa of his central London apartment. “Had someone told me back then I’d be able to produce 22 books, I’d have said that wasn’t going to happen, so I’m a little bit proud of myself.”

You get the impression Howard wouldn’t change his relative late bloomer status, though. He’s of the opinion that some people get better at certain things with age. For Howard, one of those things, he says, is marriage. He had been married twice previously, but after tying the knot for the third time aged 60 he knew he hadn’t truly been ready before. “I’m convinced it will be my final marriage. At 60 I was ready to be a human being. I reckon by 95 I will be fit to live.”

A fascinating concept

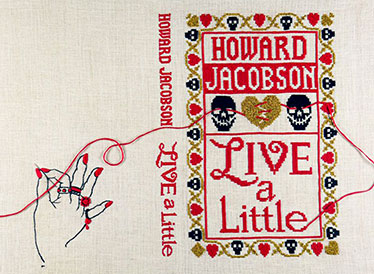

Howard’s fascination with age – he admits he's always been attracted to older women – has informed his latest novel, his sixteenth, entitled Live a Little. It tells the story of a relationship between a man and woman in their nineties. He, Shimi, is a part-time fortune teller who remembers everything, though wishes he couldn’t as he’s ashamed of things from his past. She, Beryl, is a former English teacher beginning to forget things, particularly words, which is upsetting given her interesting – even scandalous – life. She attempts to close the increasing gaps in her memory by writing a diary.

“I didn’t set out to rescue older people from imputations of elderliness or weakness or pity, that wasn’t my objective,” he explains. “My first objective is always to entertain, to make people laugh and to have insights that are funny – but also, you hope, penetrating. I suppose I got interested in writing about 90-year-olds not because I’m there myself – I’m on the way! – but increasingly I know people of that age, whose intelligence and wit surprises me more than it should. It just shows that I, too, over the years thought that at 90 you’re pretty well…”

He tails off deliberately.

“You’re not pretty well anything,” he starts up again. “You’re as fit as you allow yourself to be, or your health will allow you to be. One of my very closest friends turned 90 the other day. He’s been a writer and a journalist all his life. I send him things I write to see what he thinks, and he’s terrific about them.”

Howard’s own mother is 96. His mother-in-law is 106.

The benefits of age

“I really like ageing,” admits Howard. “I’ve enjoyed the whole experience of ageing, apart from the stiffness in the joints and the difficulty I have getting out of a taxi. Or getting up from a table. Or the need to always have change for a public toilet in my pocket. If I could set all that aside, the business in my head of ageing is so much better than being young. I didn’t get on with being young, it didn’t suit me. I didn’t like my head being full of all the nonsense you have when you’re young. I couldn’t wait to be old.

“I’m quieter. I’m wiser. I know more. I’ve seen more. I’ve listened.”

Writing: the world’s least ageist profession?

“Sometimes people say that writers lose a bit when they age,” says Howard to the question of the currency age has in writing. “I think artists – musicians, conductors, painters, and indeed novelists – can generally go on doing well. Illness can bring us all up short in our trek, of course, but if you have a little bit of luck and your mind stays in reasonable condition, you can keep doing your work. Indeed, as things afflict you, you can use that affliction to your effect. I hope to keep on writing until I drop. I hope the last thing I do is to write a sentence.”

He thinks for a moment and corrects himself.

“Actually, I’d give my wife a kiss and then write a sentence.”

Live a Little is out now and published by Jonathan Cape.